Sew Happi!

Koki Atcheson | She/Her/Hers | Honpa Hongwanji Hawaii Betsuin

My go-to fun fact is that I like to sew clothing. I love the way something flat like fabric can come together to adorn the three-dimensional body. Plus, using my hands to create something to be worn feels like a gentle, abundant act of resistance to fast fashion. Despite these motivations, my unfortunate pitfall with sewing is that I easily fall into a pattern of agreeing to projects that I can’t see to the finish line. I was in a rut of half-baked ideas and quarter-commitments when Devon asked me if I would be willing to sew happi for him and KC to wear at the opening ceremony for Irei: National Monument for the WWII Japanese American. However, after reading more about the project and remembering my own expressed desire to sew something for YBE, I agreed, knowing that I had a supportive Aunty who might be willing to help through the technicalities. I could find the time and drive to complete this project knowing that I could count on her and that my YBE family was counting on me.

Koki measures fabric to be cut for happi.

Happi (coats) are half-jackets that are often worn for festivals or to signify belonging to a group, such as a taiko ensemble. Growing up, I thought happi was written in katakana and was named after the happy feeling you get when you wear one, but the kanji literally means “half coat.”

I asked my Aunty if she would be willing to help me sew two more happi—she had already been a champion happi sewist for the Hawaiʻi Buddhist Women’s Association’s Make Me Happi project—and she agreed! The next task would be to select the appropriate fabric for the occasion. I knew I could go to a fabric store and purchase something appropriate, but I wanted to see if there were any nice pieces remaining after the fabric sale my mom and aunties helped organize at my home temple, Honpa Hongwanji Hawaiʻi Betsuin. Shoot! I thought as I first walked in. My mom’s approach to cleaning, which I’d describe as a more agitated Marie Kondo method, had worked on this room. This was ultimately a positive change as it opened up the space for more activities, but in this case I wished the bags and boxes of secondhand fabric I had seen earlier in the year remained. I had almost given up when I saw one last bag with the fabric that would be perfect to use for the happi! Its muted black background with earthy circles and gold flowers seemed like such a good match that I had to ask myself if I was just being lazy and avoiding going to the fabric store. No, I love going to the fabric store, so this print must be meant to be! Devon, KC, and Devon’s sibling Maddie (who would later complete the happi by painting a YBE insignia on the collar), all agreed that it would work.

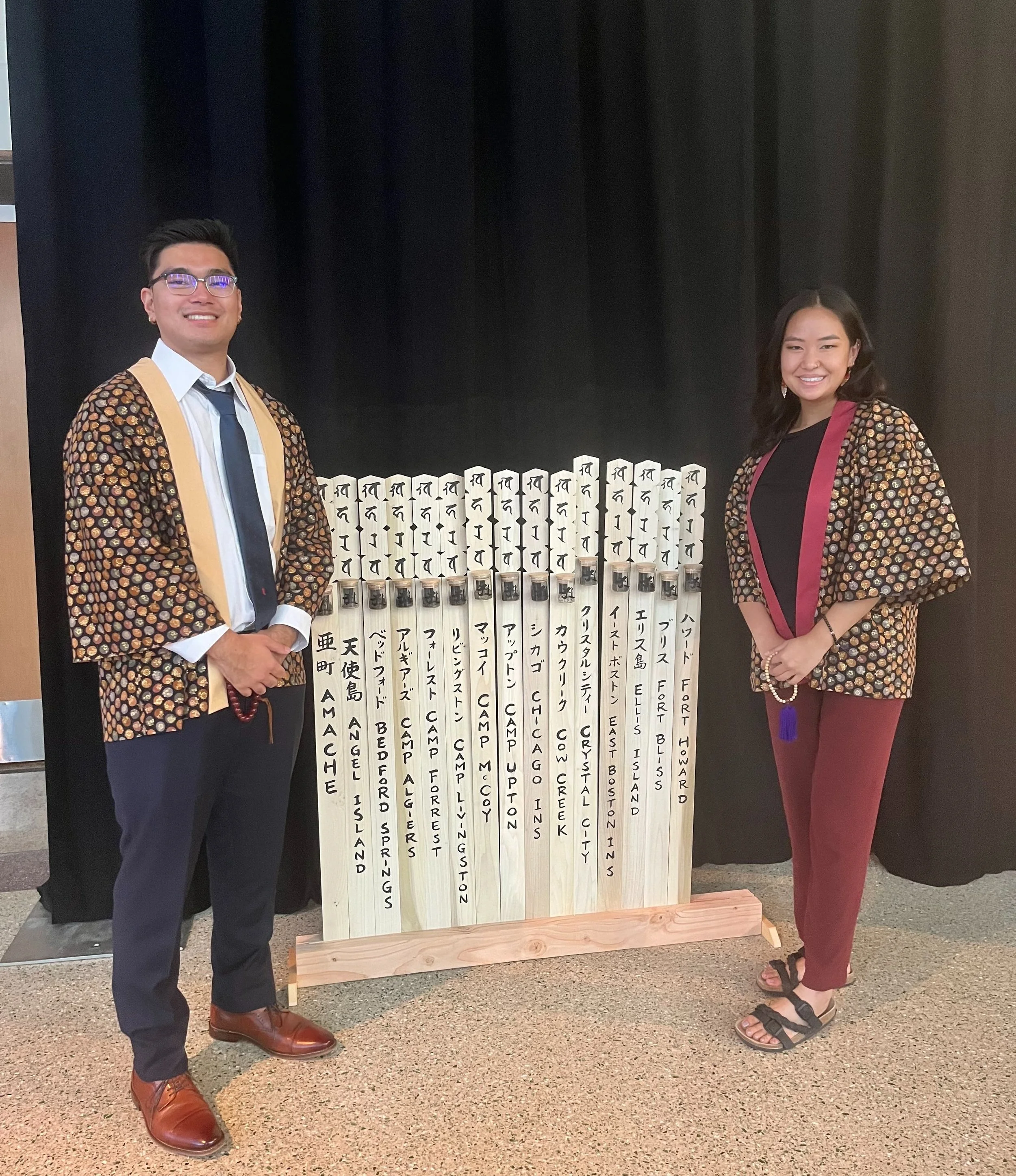

KC wears happi sewn by Koki and her Aunty and painted by Maddie.

Devon wears happi sewn by Koki and her Aunty and painted by Maddie.

I brought the fabric over to my Aunty’s house, where she has a beautiful sewing cutting table with a view, a serger which helps to make finished edges, and tons of sewing expertise. We carefully measured out the pieces for both KC’s and Devon’s happi, and fortunately the piece I had found would be just big enough with some careful planning. My Aunty is much more patient than I am with cutting and measuring the fabric, and she reminded me to take care with my work and sew with good energy. After a break for Nuʻuanu Okazuya bento, we finished some last seams and decided to call it a day. Sewing with love takes time, but I was encouraged to finish them so Maddie would have plenty of time to paint them before the event.

When I was at the post office preparing to mail the happi, I found myself thinking about my family’s experiences and perspective on WWII. The story I’ve been told is that my maternal grandparents were lucky to avoid internment because of their living situation in rural Utah, where the Japanese community was sparse and isolated to the point of the US government not considering them a threat, and because my grandpa’s role as the town doctor made him too essential to remove from the community. I haven’t heard this story firsthand from my grandparents because WWII and internment were not topics they were willing to discuss. I’ve wondered if they avoid talking about it because of pain, shame, guilt, some combination of those, or maybe something else entirely. I know my mom shared my curiosity because she sought out this history through work with Omoide, a Seattle-based project that documented personal narratives of Japanese Americans incarcerated during WWII. I see this as her way of trying to patch the personal and community history that was not openly discussed.

I find myself seeking ways to mend gaps in my connection to Japanese American history, too. Within this project, I can’t ignore the connection of relying on Jodo Shinshu aunties and fabric donated to a Jodo Shinshu temple to outfit my Dharma friends in a ceremony that recognizes Japanese American ancestors. As I reflected on the experience of creating these happi, I found deeper ties between craft and history, and in turn, deeper motivation to keep sewing. The loneliness I feel from not directly knowing my grandparents’ experiences through internment is healing from the curiosity I find in connecting with Japanese American communities today. Devon and KC mentioned what an honor it was to be invited to participate in the ceremony, and I too felt honored to help create their outfit with my most cherished sewing Aunty.