KEETLEY, UTAH

Contributed by E. Katsumoto | February 16, 2021

Most accounts of the E.O. 9066 evacuation experience are about those who spent the war years in war relocation camps after being forcefully removed from the security of their homes along the West Coast. My family was one of the relatively few that was able to self-evacuate on their own, which was allowed by the government if this could be accomplished within a relatively short lead time before others were forced from their homes. I was born in Utah during this diaspora and thus my account is all secondhand and from pictures and articles of that period. Luckily my historian cousin wrote a very detailed account of our family’s self-evacuation after wisely interviewing his mother before she passed. This account is partially a summary of what my cousin wrote.

My father was the eldest of 12 children, so we have a large extended family. In the period before the attack on Pearl Harbor, our relatives were living in various parts of California: our family in Oakland, and others in Gilroy and Lompoc.

The frightening rumors relayed to my widowed paternal grandmother frightened her and led to her decision to take advantage of the opportunity to self-evacuate to keep her family safe and intact.

She sent her son and son-in-law to check places in Utah to which we could possibly evacuate; we already had some friends living in Salt Lake City. While there, they serendipitously encountered Fred Wada who was also searching for places to evacuate his family and friends to form a farming community. After checking on several possible areas, they decided to join forces to settle their respective parties at Keetley, Utah, (now buried as part of the Jordanelle Reservation Dam) a former mining area that had some existing homes and a large boarding house for former miners. This could conveniently accommodate the 130 people who would evacuate with them, and the surrounding land could be cultivated. Another advantage was that Keetley had a train depot which would allow the evacuees to separately transport their belongings by freight. The other potential sites they had investigated held overt discrimination and antagonism towards a sudden influx of Japanese into their community. Mr. Fisher, the owner of this property was sympathetic to the Japanese and leased his ranch with 4000 acres to this large group for $7500/year. After the financial arrangements were made, my uncles returned to Oakland to report back to Obaach and and to help get the preparations started.

Children in the initial Keetley Group

They only had a few weeks to make all the arrangements.

There was a mad scramble to obtain the many travel permits required for each person and to arrange for their possessions to be loaded onto the train for transporting to Keetley.

My father’s family uploaded essential furniture, bedding, food items (such as sacks of rice, shoyu, canned goods, etc.) onto the boxcars, storing other personal belongings in the back of the garage. My father had just purchased a home in West Oakland whose escrow had luckily closed right before the Pearl Harbor attack. He was able to rent it out during our absence. Before departure to Keetley our relatives gathered at this house, now stripped of beds and essential furniture where they all slept on the floor the night before leaving. Rumors were rampant that any suspicious movement would be dangerous, so they left in cars in the stealth of night in caravans of four to five vehicles at a time, defying current curfew restrictions. Thus, early in the morning of March 29, the final day that self-evacuation was allowed, this exodus to Keetley consisted of 54 relatives in the Endo group to later join the Wada group of 59 people. (Other relatives joined the family later, making the Endo group 63 in total.) This group departed in 17 cars, 11 trucks, and two trailers. My uncle was only 15 and without a valid drivers license, but he was enlisted to drive one of the cars.

The group leaving from Oakland spent their first night at a motel in Truckee, which was owned by German immigrants. They were sympathetic to their plight, so our family had no problems there. They spent their second night in Wells, Nevada, and luckily encountered no problems with lodging, food or buying gas en route. It was still frightening, especially for the women, as they did not know what hostilities they might encounter.

My mother and her sister were both pregnant and felt especially uneasy.

When they reached Keetley, they discovered grounds covered with snow and buildings in dilapidated condition. Adjusting to their new living environment was challenging, and the women soon learned that cooking rice on wood-burning stoves took much longer because of the 6000-feet elevation. Luckily my uncle had packed a lot of his non-perishable food goods onto the freight car from his grocery store in Oakland, so their immediate food needs were met. The only vegetable initially available was cabbage. My father later recalled that he was amazed how the women were able to feed their families under these conditions.

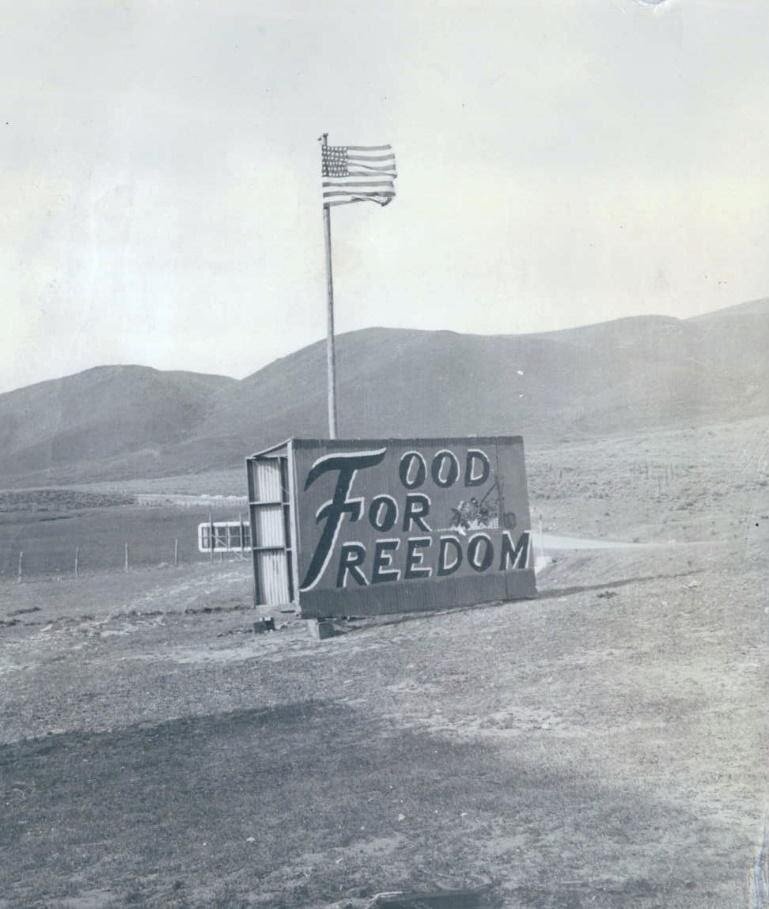

When the spring snows melted in Keetley, they revealed a very harsh land filled with many rocks and sage brush that needed to be cleared. They got to work, toiling 16-18 hours daily to make the land more cultivatable with the farming equipment they brought. They planted their first crop, but the yield was very disappointing and profited only about $10/person for this group of 130 people. So after three months our family and some others from the Wada group decided to leave and fend for themselves in other areas, but the Wada Family continued on at Keetley. While neighbors initially were suspicious about our group, they slowly warmed up as they saw the bountiful crops being grown in Keetley. Local publicity became positive and featured pictures of their patriotic Food for Freedom efforts.

Flag @ junction of Keetley/US 40

Our family left Keetley in June, just three months after first arriving, and first went to Sandy where they were able to lease three acres to farm. Their first crop of tomatoes was doing well until they lost all of it to an early frost. They again reached a critical crossroad. Could they really be successful farmers? One uncle eventually bought a farm in Midvale and continued farming while my father and his brother decided to find jobs in Salt Lake City working in the service industry as pressers. They rented an apartment with one bed and took turns sleeping in it as their various shifts allowed. Then they would visit their families on the weekends. By then there were four children in our family, and then I was born making it five. Eventually my father found a house in Salt Lake City to rent, so this is where we lived until we were able to go back to Oakland in 1946 after the war ended.

We were always surrounded by our extended families with each move, so life was bearable within our close-knit family. However, it was not always without worries and uncertainty about how to survive. To draw some comparisons, though camp life had its indignities and lack of personal freedoms, the internees did have housing, however inadequate, and regular meals however tasteless in the beginning. Opinions of this period from the people affected depends on the age group interviewed. Amongst the Nisei who were incarcerated in the relocation centers, there seems eventually to have been some social structure and even social life with so many Japanese living in one camp site, fairly sheltered from ethnic discrimination from the dominant culture.

My family related that while they found Utahns to be mostly accepting, the younger children experienced some bullying and discrimination in the schools they attended.

My uncle (the one who drove the car to Utah without a license) became a major basketball player at Jordan High School, but local parents objected to having a JA on the team and he was thus prevented from playing. Another Japanese student was prevented from giving the valedictorian speech at her high school. However, there were also good experiences of neighborliness and friendship amongst the people of Utah, and luckily my family did not experience any undue hardships of discrimination. The point is that despite self-evacuees having their personal freedom during this period, it was as challenging a life as it was for internees, but difficult in different ways. The thing that helped both groups to survive was the enduring strength and guidance of the Issei and the strong cultural values that helped all to survive this hateful period in the history of the Japanese Americans after December 7, 1941...